I am compulsively devouring phrases. I gobble up expressions like me da pena (it upsets me) and qué buen rollo tiene (how nice he is). It’s not just my reading of the literature on phraseology that impels me. It’s a gut-feeling that these phrases offer a shortcut to fluency, accuracy and idiomaticity.

I am compulsively devouring phrases. I gobble up expressions like me da pena (it upsets me) and qué buen rollo tiene (how nice he is). It’s not just my reading of the literature on phraseology that impels me. It’s a gut-feeling that these phrases offer a shortcut to fluency, accuracy and idiomaticity.

As a youngster I was a nerd avant la lettre, and used to collect phrases from books I was reading, which I would then try to work into writing assignments at school (what now would be called plagiarism). Richmal Crompton’s Just William series was a particularly rich source. I remember co-opting the expression ‘in my official capacity’, much to the bafflement of the teacher, since I had no official capacity whatsoever.

But, even if misapplied in this instance, it was probably a sound learning strategy, and certainly one that is now a fundamental tenet of ‘the lexical approach’. As Pawley and Syder (1983) were among the first to argue, pre-fabricated phrases confer not only idiomaticity (in the sense that they make you sound more target-like) but they also aid fluency: pulling down whole phrases off the mental shelf represents big savings in terms of processing time.

More recently, researchers into both first and second language acquisition have been arguing that a ‘mental phrasicon’ not only contributes to fluency but also feeds the acquisition of grammar. According to this view, a fully syntacticalized grammar is (at least partly) constructed out of, and synthesized from, a stock of memorized phrases.

As Nick Elllis (2003, p. 67) puts it, ‘the acquisition of grammar is the piecemeal learning of many thousands of constructions and the frequency-biased abstraction of regularities within them’. In other words, memorize a chunk like ‘you must be kidding’, and you not only have a useful conversational gambit, but you are getting the raw material, in prototypical form, out of which you can extract ‘you must be joking’. It’s a short step to ‘it must be raining’ and ‘they must be closing’.

This is true for first language acquisition and, arguably, for a second language too. ‘From the perspective of emergent grammar … learning an additional language is about enhancing one’s repertoire of fragments and patterns that enables participation in a wider array of communicative activities. It is not about building up a complete and perfect grammar in order to produce well-formed sentences’ (Lantolf and Thorne, 2006, p. 17).

(How I wish that that quote were emblazoned across the gates of our leading publishers and examination bodies!).

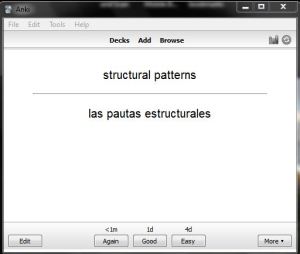

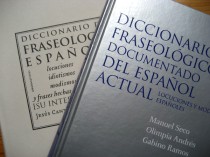

Accordingly, I decided from the outset to keep a notebook of phrases: ones that came up in class, or ones that I noticed in my out-of-class reading. I reinforced my stock of phrases by reference to two fat Spanish phraseological dictionaries. I keyed these all in to Anki, an excellent tool to aid memorization, which digitally replicates Paul Nation’s ‘word cards’ technique, randomizing the sequence, and calibrating the time lapse between items, on the principle of ‘spaced repetition’, according to your own assessment of the accuracy of your recall. (For more on Anki, see this link).

Accordingly, I decided from the outset to keep a notebook of phrases: ones that came up in class, or ones that I noticed in my out-of-class reading. I reinforced my stock of phrases by reference to two fat Spanish phraseological dictionaries. I keyed these all in to Anki, an excellent tool to aid memorization, which digitally replicates Paul Nation’s ‘word cards’ technique, randomizing the sequence, and calibrating the time lapse between items, on the principle of ‘spaced repetition’, according to your own assessment of the accuracy of your recall. (For more on Anki, see this link).

The problem is that there didn’t seem to be any real selection criteria, and hence no organizing principle, for the phrases that I was collecting and attempting to memorize. The dictionaries I consulted gave no indication as to the relative frequency of the phrases nor their register, although one of them at least had examples taken from authentic sources. But, basically I was choosing anything that sounded like it might be useful, especially those phrases – like no le caigo bien (He doesn’t like me) or yo tengo claro que… (I’m sure that…) – that would confer a degree of idiomaticity, without being too colloquial.

In light of the reconfigured objectives mentioned in the last post, i.e. the focus on presentation skills in Spanish, I decided to limit my ‘phrasicon’ to chunks that might be useful in terms of their relevance to the twin fields of language and learning, as well as chunks with high discourse functionality. That is to say, I wanted words and phrases that would help me talk about language teaching and that would also help organize and signpost this talk.

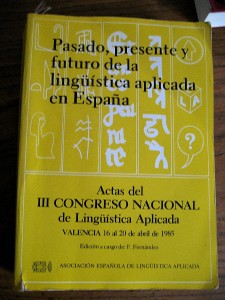

But where to find them? By chance, rootling around in a second-hand bookshop in Barcelona, I came across a copy of the proceedings – in Spanish – of a conference on applied linguistics, convened in Valencia in 1985. A quick glance confirmed that what applied linguists were talking about in 1985, such as puntos gramaticales (grammar points) and un enfoque comunicativo (a communicative approach), is still very much what they are talking about now. Moreover, although the papers are (obviously) in the written mode, there seemed to be a good number of discourse markers, such as en primer lugar (in the first place) and veamos un ejemplo (let’s look at an example), that might be equally useful for giving semi-formal spoken presentations.

But where to find them? By chance, rootling around in a second-hand bookshop in Barcelona, I came across a copy of the proceedings – in Spanish – of a conference on applied linguistics, convened in Valencia in 1985. A quick glance confirmed that what applied linguists were talking about in 1985, such as puntos gramaticales (grammar points) and un enfoque comunicativo (a communicative approach), is still very much what they are talking about now. Moreover, although the papers are (obviously) in the written mode, there seemed to be a good number of discourse markers, such as en primer lugar (in the first place) and veamos un ejemplo (let’s look at an example), that might be equally useful for giving semi-formal spoken presentations.

So, using this book as my ‘corpus’, I created two decks of word cards in Anki: academic collocations, and academic discourse markers, to which I added a third called academic sentence frames, which aims to capture constructions with variable slots that might offer templates for a degree of creativity. E.g. no hay motivo para pensar que… (there’s no reason to think that…) and lo que es importante subrayar es… (what is important to underscore is…’

I’ve been reviewing and supplementing these three decks while on planes and in airport lounges, as I travel round Australia on a conference junket. Having the Anki app on an iPad is ideal for this. Apart from anything else, you can synchronize the app with your home computer, keeping both up-to-date with new entries.

Is it working? Yes and no. Recall of the phrases seems good in the short-term, but if I leave them a day or two, many of them have to be re-learned from scratch.

I suspect that the only way of making them stick is to force some kind of production, preferably in context. But what? Maybe I need to write, rehearse and even record short (e.g. two-minute) segments of talks that embed as many of the phrases as possible. Any thoughts?

Ellis, N. (2003) ‘Constructions, chunking and connectionism,’ in Doughty, C. and Long, M. (eds.)The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, Oxford: Blackwell.

Lantolf, J. and Thorne, S. (2006) Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pawley, A. & Syder, F. (1983) ‘Two puzzles for linguistic theory: nativelike selection and nativelike fluency,’ in Richards, J., & Schmidt, R. (eds.) Language and Communication. Harlow: Longman.

October 6th, 2013 at 9:37 am

Enjoying following you on this particular learning journey, Scott. I work for a publisher as you know, but hey, I don’t bear grudges when you throw in the regular references to us 🙂 Anyway, take this as a bit of peer-to-peer correction from another long-term native English speaker struggling to perfect his Spanish, but “no le caigo bien” is actually the opposite of what you suggest, and something more along the lines of “he doesn’t seem to like me”.

(Thanks for the pointer to Anki, by the way. Looks well worth checking out).

October 6th, 2013 at 9:42 am

Thanks, Mark, for kicking off the discussion – and the correction. Oops! (I’ve amended the text… but your comment still stands!)

October 6th, 2013 at 9:52 am

If you go about learning this way, Scott, you’ll undoubtedly soon be able to give presentations in flawless Spanish (mainly those you can prepare in advance, though) until someone stops you and asks a spontaneous question 🙂

Michael Swan (2006), for example, argues that it might seem disappointing, but most non-native speakers must settle for the acquisition of a variety characterized by a relatively restricted inventory of high-priority formulaic sequences, a correspondingly high proportion of non-formulaic grammatically generated material, and an imperfect mastery of collocational and selectional restrictions. We cannot do anything about it, he argues, languages are difficult and cannot be learned perfectly. (http://bit.ly/K58nSK, section on Realism and Prioritising).

October 6th, 2013 at 10:15 am

Thanks, Hana, for that comment – and the link to the Swan article, which is a useful, and well–argued, corrective to the view that lexical chunks will ‘surrender’ their grammar, ‘for free’, as it were. I particularly like this bit, not least because the person who made the pineapple quip was me!:

(In the collection of papers by Swan that OUP published last year (Thinking about Language Teaching) he kindly restores the attribution).

While I do mostly agree with him (especially his point that native speaker phrasicon is an impossible target) I am not so sure that grammatical patterns can’t be inferred (or abstracted) from phrasal chunks, especially if these chunks are (a) prototypical; (b) generalizable (i.e. not grammatical one-offs like ‘come what may’) and (c) subject to conscious attention and study: this last point is key: you need to attend to the pattern, and perhaps manipulate it in some way: e.g. no le caigo bien (he doesn’t like me) -> no me cae bien (I don’t like him) -> no es que me caiga mal, es que no le caigo bien (it’s not that I don’t like him, it’s that he doesn’t like me) and so on. This is where a tool like Anki has only limited application. (Corrections accepted, by the way!)

October 7th, 2013 at 10:26 am

As a footnote to the above point about the limitations of an ‘exemplar-based’ approach to learning, where exemplars take the form of phrasal chunks, it’s worth cutting and pasting this comment I made in the thread C is for Construction, in An A-Z of ELT:

October 6th, 2013 at 10:15 am

I find the anki cards are a good review tool but in order to get the words into your brain you really need to do a lot of work memorizing and using the phrases/ words initially to get them over from passive to active vocabulary.

Have any of your books been translated into Spanish? Would your own thoughts and ideas already translated into native level Spanish not be the perfect learning tool to help you express the things that you want to say?

I also noticed that you set up your cards to go from English to Spanish, I there any reason you chose not to do Spanish to English? Or for that matter Spanish to Spanish ( definitions taken from Spanish dictionaries)?

October 6th, 2013 at 10:40 pm

Hi Scott… yes, you’re right about doing the spade-work (and your comment more or less coincided with my response to Hana above).

My books have been translated into Chinese, Japanese, Thai and even (soon) into Basque, but not (as far as I know) Spanish. However, a commentator once posted on my other blog (An A – Z of ELT) a concordance he’d made of an article of mine using Google Translate, in order to throw up the most frequent words, i.e. ones that I might want to learn if I was to talk about the same topic in Spanish. You can see the comment here:

Finally, re the point about the direction of languages, yes, the beauty of the (physical) word cards is that you can use them in either direction (L1 – L2, or L2 – L1). I know you can do this with Anki too, but I have yet to find the tool that allows this.

October 6th, 2013 at 10:17 am

Hi Scott,

I can completely identify with this need for production in order to make things really stick. To develop my Spanish vocabulary I’ve been using http://www.memrise.com , which is bit like Anki but with the added bonus that many of the words and chunks are presented with mnemonics that other users have already keyed in. There is also the option of feeding in your own mnemonics for the words you are learning.

We have a Spanish couple staying with us at the moment and the other day I wanted to tell them about leaving the windows open a bit during the day to stop mould building up on the walls. I knew I’d encountered the word for mould (moho) on Memrise and had successfully retrieved it many times but now when I actually needed it I couldn’t quite pluck it from memory. All I could remember was that it started with ‘M’ so I started saying the word and Joaquin understood what I meant and said the word himself. This necessity to use the word in context seems to have built up much stronger memory traces than decontextualised retrieval through memrise and I’m pretty sure I’d remember moho now if I needed it again.

In a couple of weeks I’m going to be spending a week in an Arabic speaking country. This isn’t a language I know at all but I’m thinking of building up some high frequency key words and phrases through flash cards before I go, and then trying to throw myself into situations where I need to use them when I’m there. What do you think?

Nick

October 7th, 2013 at 10:34 am

Hi Nick –

This sounds like an excellent strategy – but where will you access these words and phrases? Be warned that what is called Modern Standard Arabic (in textbooks, grammars etc) bears little relationship with what is spoken on ‘the Arab Street’. You’d be better off getting a phrasebook specific to the country you are going to, and using that as your flashcard source.

I’ll be keen to know how you get on!

October 7th, 2013 at 1:36 pm

Thanks for that tip Scott. I’ve got a fairly country specific phrasebook and am now in the process of picking out some key chunks to make flash cards with. I’m going to go for simple paper flash cards for the flexibility this provides in the when, where and how of the retrieval.

October 6th, 2013 at 10:27 am

I’ve been enjoying your blog and comparing degrees of fossilization.

My experience of learning Spanish is quite different from yours. I came to Spain because I’d met my Spanish partner. He spoke no English and I spoke no Spanish – we communicated at first in French.

After living 32 years in Spain (Seville) I’m very aware of the fact that I can communicate effectively – most of the time. But, as my Spanish is far from accurate, misunderstandings arise which actually cause communication to break down. Trying to remember verb endings is one of the main culprits (as far as I’m aware!) – hizo/ hice / fue / fui –Who the hell are we talking about? Why can’t we just use subject pronouns??

My first experiences of Spanish classes at the Seville University in 1980 were disastrous – apart from the teacher arriving 15 minutes late to every class and making the time up at the end of the class when I had to leave to teach – I was a total beginner and everyone else already spoke Spanish. But I do vaguely remember that the classes were based mainly on grammar exercises and asking my then boyfriend to explain the homework – subjunctives and imperatives –totally impenetrable. So zero to Seville University as far as language learning goes at this point.

This is when I was also learning to be a teacher and stumbled upon Krashen – Yes, immersion can lead to language learning, of a kind. After being bored to …not to death, but yes, to falling asleep in get-togethers with groups of Spanish speakers and also hours of torture watching TV in Spanish (I would not recommend this method of language learning as I feel I may have been traumatized by watching endless episodes of ‘Hombre Rico Hombre Pobre’, ‘Penmarik’ and ‘Dallas’) I do distinctly remember that after about 6 months I could actually start to participate in conversations in Spanish – more on a one-to -one level than follow conversation in groups. Did immersion work? Did language acquisition happen? Yes, but my Spanish was extremely limited.

In 1983 I once again started classes at the Instituto de idiomas of the Universidad de Sevilla. This time with greater success. There was a level test and I was in a group of students with a similar level. The teacher was great – friendly, approachable, punctual and he gave interesting and varied classes. I have recently found my Spanish books and was amazed to see compositions with very few errors and high marks! Learning how to use the subjunctive was not the main objective of the course.

Back to Krashen – I was never convinced by his theories – OK, being immersed in a new language did facilitate my language learning, but only at a very basic level. Do we become expert language users of our ‘mother tongue’ without a lot of reading, writing and effort to perfect our language abilities? Clearly we do not. I believe it’s impossible to use Spanish accurately without studying and practicing the language – after two years at the Instituto de Idiomas and doing my homework regularly, my Spanish friends commented on my improved abilities! I must admit I have often felt like telling Krashen where to put his misleading ‘language acquisition’ theories! Or maybe I’ve misunderstood Krashen.

Enter my son in 1985 plus the opening of my own little school in 1988 and exit my Spanish language classes! As I have been able to run my very small language school with my limited Spanish I no longer felt the need to return to classes – also, my lack of proficiency in Spanish is sometimes seen as proof that I am actually a ‘native’ speaker! A mother, over the phone, once accused me of being Spanish and non-native! I was very flattered but of course, not good for business!

Recently I have had a bit more time and have become more aware of the weaknesses in my Spanish language abilities: speaking with Spanish friends and an English friend who speaks Spanish accurately – these weaknesses have been kindly brought to my attention! Kindly because I have decided I want to improve my Spanish and up to now no one has corrected me – and we all know what a drag it is to try to have a conversation but have to make the effort to correct someone when all you want to do is have a chat and relax!

Scott’s blog is my new starting point (or ‘punto de partida’ – I often find I can no longer speak natural English – not only is my Spanish ‘fossilized’, my English is too – unaware of many of the latest English expressions *- and speaking English that’s all jumbled up with Spanish word order – but that’s another blog)

Whenever I go back to the UK I become aware that most Brits would have a hard time passing the B2 exam…it’s amazing how many people never use participles – I’ve observed that they barely exist for many of my fellow Scots: ‘Have you saw that new film?’, ‘I’ve never went there’….and no one is ‘rasgando las vestiduras’ ( you see, once again – some phrases just come to me in Spanish. Is this because my English has not so much fossilized as atrophied? Or is it because some phrases just express a specific idea better?) B ut I digress. The question is what is effective communication? How accurate does language have to be?

So, after reading today’s blog, my conclusion so far is that the ability to communicate effectively and accurately is the result of a lot of conscious effort to learn specific language patterns (e.g. irregular verbs) plus a lot of exposure to the language and opportunities to use the language. Also, I suspect, there could be a love of language and curiosity which means that certain patterns ‘te llama la atención’ so that they stick in your mind more. Yes, I have to add as an English teacher who’s spent a long time in Spain – idiomatic English has also become an issue!

Anyhow Scott – your blog has made me think a lot! Thanks!

* for example: I hadn’t a clue what a ‘muff diver’ was and had to ask my niece at a show at the Edinburgh Fringe last month – not that this impeded communication, ‘una imágen vale más que mil palabras’

October 7th, 2013 at 10:39 am

Thanks, Lorna, for that fascinating insight into your development as a second language user. It prompts me to suggest that the three ingredients that are necessary for second language acquisition are simply: exposure, study, and use (where use includes feedback). Any two on their own (e.g. exposure and use) don’t work – or work only with certain individuals, or only to a certain limited degree.

October 6th, 2013 at 10:30 am

Hi Scott,

Your struggle to find a sequence or organising principle for your phrases is the same problem that has existed for syllabus/coursebook writers since the dawn of the communicative approach, and the reason why the grammatical syllabus still rules. This does my head in.

I am, however, very encouraged by the way you have chosen to approach it as a learner – having identified your L2 self you have focused the content of your input on what you specifically need to know. I wonder if this is a strategy that we could explicitly focus our learners on in a classroom context – get them to read/listen to/watch language in use based on their individual needs/goals/L2 selves, then select and create their own phrasicons.

With regard to actually acquiring the phrases, surely this can only occur through practice. But again this can be done in class through project work – after the receptive phase where phrases are identified, students could produce something (a presentation, an essay, a documentary, a play – whatever) that facilitates the use of the phrases they selected. The class would get to see each other’s projects and make comments, allowing for some peer teaching of language to reinforce learning.

Language would be contextualised from the start, and this approach would demonstrate real individualised learning within a group. The focus on specific language needs and preferences would (probably) increase motivation.

What do you think?

October 7th, 2013 at 10:45 am

Hi Steve, yes I totally agree, and this is where a task-based approach and a semantic syllabus consisting of constructions (so as to include not just exemplars but patterns, i.e. chunks AND pineapple) would seem to be a marriage made in heaven.

My experience giving a presentation in my Spanish class alerted to me as to just how powerful this sequence could be:

1. choose topic

2. research useful phrases

3. rehearse

4. present

5. get feedback

6. revise presentation

7. present again

October 14th, 2013 at 6:23 pm

If what Steve describes above isn’t the lexical approach in action (using the TBL framework) I don’t know what is then 🙂

L

October 14th, 2013 at 8:43 pm

It involves viewing language lexically, yes, but there’s more to it than that. The priority as I see it would be to ensure that the language learned is the language that needs to be learned. It’s important that it comes from the learners and not from anywhere else.

October 6th, 2013 at 11:03 am

Good morning, Scott:

you’re working hard, but I imagine you a bit like playing tennis by yourself. If you practice a two minutes talk on linguistics or whatever, there’s nobody on the other side that can tell you: “Well done, Scott, but X doesn´t sound like Spanish, nobody uses an expression like Y”, etc.

Definitely, you need a partner to play with. And specially, as Hana points out, if you’re going to allow questions from the public after your talks.

Te lo estás currando muchísimo, pero me da pena imaginarte jugando solo 🙂

October 7th, 2013 at 10:51 am

Hola,Beatriz.

Sí, por supuesto, necesito alguien con quien pueda practicar. La búsqueda de la persona más adecuada será el tema de otro ‘blog’.

October 6th, 2013 at 12:45 pm

Hi Scott,

Like you, I live in Catalonia. During my efforts to learn Spanish, I have encountered a lot of interference from Catalan (Linguistically rather than politically). The result is that my Spanish is often peppered with Catalan chunks. This isn’t always a problem because the people where I live seem to understand me,

I have witnessed similar problems amongst students who study German as well as English. I don’t know if there is much literature on L3 or even L4 interference.

Has this been an obstacle for you? And if so, do you have any strategies to combat it.

October 7th, 2013 at 10:56 am

Hi Matt,

Good point: the challenge of learning a second language in a linguistically variegated context such as Catalonia is perhaps different than if you were living in a monolingual society. Occasionally in my Spanish class I would amuse the teacher by accidentally using a Catalan word (e.g. pollastre for pollo [chicken]) but this didn’t happen much – perhaps because I haven’t been exposed to as much Catalan as you may have. Where it does affect me is in terms of practice opportunities: I spend most weekends in a town where Catalan is the dominant language, and this severely inhibits my opportunities to speak Spanish. (‘Learn Catalan, then!’, I can hear my critics bellow!)

October 6th, 2013 at 1:30 pm

Hi Scott,

Just quickly, re Anki – perhaps try out Quizlet, http://quizlet.com/ this is the one I recommend to my students as along with flashcards there are learning games, spelling practice and more importantly, you can use pictures as well as definitions/translations. That might help out in terms of setting up a context as you mentioned…

Also, a somewhat sneaky trick I remember doing when I was learning Spanish revolved around noticing filler words. Years ago, I found that I would be speaking in Spanish at a relatively good speed, comfort and okay range of vocabulary and then smack in the middle of an interaction, I would say an English filler, for example, “well” instead of “pues”…so to undo that I started paying attention to these small itsy bitsy words (e.g. sabes? mira, tipo) and even worked on the accent on non-words (e.g. em), and then would take care to pepper these into conversation, which I think made me sound more fluent than I was really… 😀

October 7th, 2013 at 11:11 am

Thanks for the tip re Quizlet. I’ll check it out.

Re conversational fillers: yes, you are right in thinking that these give an illusion of fluency, and I have gathered a few myself. However, the illusion of fluency may in the end be counterproductive:this is suggested by some of the studies of the use of communication strategies (including pause fillers etc) by learners. As Ellis (1994: 403) comments ‘Learners like Schmidt’s [1983] Wes have been found to develop their strategic competence at the apparent expense of their linguistic competence’. Still, as with the use of gesture, the ability to sound (and look) like a fluent speaker might open up more opportunities for practice than if your delivery is painfully slow and halting.

October 7th, 2013 at 10:57 pm

Ah, I didn’t know that. Thanks, but yes the second part is also true, as I did get more opportunities to speak with native Spanish speakers, as they were less likely to go to English to accommodate my lack… all rather interesting!

October 6th, 2013 at 4:21 pm

Hi Scott,

Like Karen, I do really recommend Quizlet for one additional (very good!) reason,which is that Quizlet flashcards CAN TALK! And not just in English or Spanish, but in a host of weird languages like my own (Polish). And this is possible with single words as well as phrases and even complete utterances 🙂 All one needs to do is input the text (same as in Anki) and the engine adds the sound. Pure magic …

I was fascinated to read today’s blog entry. For the past few years I’ve been piloting a project which also builds on high-frequency ‘phrasicon’ and attempts to overcome the difficulty with the oral practice that you compain about. Our answer is to focus on language of the home and practice ‘domestic utterances’ among household members. We started out with English (and so called the project ‘English for parents’ to amplify their potentially instrumental role in involving their kid(s)) and then, surprise surprise, started playing with Spanish! With Spanish, I’ve been using my own family as guinea pigs – great fun. And I can confirm what you said about the need to recycle such domestic utterances all the time lest they slip from memory. Fortunately, though,domestic language is by definition highly recursive as it accompanies a whole range of repetitive, routine, everyday domestic situations (‘Duerme con los angelitos’ can happen fully context-anchored up to 365 times a year)

Basing the project firmy on ‘domestic English/ Spanish etc’ has one additinal advantage, which to a certain extent addresses Stve Brown’s point about the difficulty of developing a syllabus around lexical chunks: our approach is to focus initially on the most frequent communicative, ‘transactional’ needs of the child(ren) – particularly those that parents are not always willing to satisfy when the request is made in L1 (‘Puedo jugar con el ordenador?’ :-)) …

Once again, thanks for your contribution – always a joy to read.

Grzegorz

October 6th, 2013 at 5:22 pm

Sorry – I clicked too quickly, before I said the main thing:

your post ties in beautifully with a project that I have been piloting for the past few years. It also builds on a ‘phrasicon’ but restricts the selection to high-frequency phrases that routinely happen as part of everyday domestic life between household members, esp. parents and child(ren).

We started out with English and so called the project ‘English for parents’, to amplify the potentially instrumental role of mum and dad in its implementation with their kid(s). We have already developed a set of Polish-English materials introducing ‘domestic English’, aimed at Polish parents and their children.

And then, surprise surprise, we took on Spanish. In this case it is very much action-in-progress and my own family are the guinea pigs. None of us spoke any Spanish when we started and there were no domestic Spanish study guides so we have to rely on a Spanish teacher friend who has been gradually translating ‘English for parents’ into Spanish for us.

This kind of ‘domestic language’ is by definition context-anchored and highly repetitive: ‘Duerme con los angelitos’ can happen naturally, i.e. when it’s needed as part of kiss-goodnight routine, up to 365 times per year! Which is great as it helps fend of the forgetting (sth that you complained about towards the ed of your post)! And also shows that internal grammatical/ lexical complexity (and length!) is not what makes a given chunk difficult, compared to its relative (in)frequency.

‘Domesticating’ English or Spanish between parents and children has one added advantage: it helps address Steve Brown’s concern re. how to plot a convincing syllabus around lexical/functional chunks. Our trick in this project is to localize the selection as much as possible, stating off with the most ‘transactionally’ attractive language FOR THE KID(s) – i.e. things that they want to get from mum and dad that they know is unlikely to happen (or at least not as much as they would want to :-)) if the request is made in L1. So we strike a deal and *agree* to grant permission if instead of Polish we hear ‘Puedo jugar con el ordenador’ – to take one very obvious example…

An now for the best part: from time to time we see how the need to ‘soften’ mum and dad is s urgent that the child attempts to use L1 as a crutch, e.g. ‘Vamos do kina?’ (= al cine) 🙂

Once again, thanks a lot for your great entry!

October 7th, 2013 at 11:30 am

Hi Grzegorz (sorry, btw, that you had to post twice: I imagine you thought the first post never made it, but in fact it was sitting in the moderation tray. I’ve now changed the WordPress settings so this doesn’t happen – it happened to Matt, above, too).

I’m absolutely fascinated by your ‘project’: I hope you will write it up. I love the idea of ‘domestic Spanish’, and this kind of narrowing of the target domain seems to be under-researched in terms of SLA. The tendency in most teaching approaches and materials is to keep the domain maximally wide (e.g. General English) which means it takes forever to achieve anything like communicative competence in it. Whereas aiming at a more restricted register might confer communicative success sooner. The question then is, how easy would it be to transfer this competence to other domains/registers? I’d like to think it wouldn’t be too hard – a but like learning to drive on the left after first having driven on the right.

October 6th, 2013 at 6:01 pm

Dear Scott,

If you are really looking for a piece of advice on how to reinforce the selected phrases through production, why not have a discussion with a Spanish-speaking linguist / teacher over a controversial topic, e.g. A language course syllabus should be mapped around grammar rules, i.e. something you feel strongly against? This kind of interaction, in my experience, stretches one’s linguistic resources to the utmost and makes the language you use extremely memorable. To focus on those sentence frames and discourse markers you have selected, have a “cardversation” – you pick up a card with a phrase and have to use it, or just have a list of them in front of you and every time you use one, you tick it.

And how about reverse translation, with your own books translated by native speakers of Spanish (a suggestion mentioned above)? It is a kind of awareness-raising activity without any heavy metalanguage terminology. Contrastive analysis in action, it might work. What do you think?

And there is another very interesting point that came up in the comments – if you say “learning an additional language is about enhancing one’s repertoire of fragments and patterns”, does it mean that one’s own native language starts deviating from the norm ( i.e. “pure” English of someone who has never studied any other language) after learning another language? I mean that your English must have become by now very different from “the monolingual norm” in the choice of structures, lexical chunks and just words because it has been influenced by Spanish. Do you notice such changes in your English?

Thank you very much for the post – it has raised a lot of related sub-issues. That’s what happens when you throw a stone into still water and it causes a few rounds of waves.

October 7th, 2013 at 11:15 am

Thanks, Svetlana. Yes, your suggestion as to how to activate my academic phrasicon chimes with my own intuitions. I am now on the hunt for a private teacher who can provide these kinds of practice opportunities. As Beatriz pointed out, I need a ‘tennis partner’!

Regarding the effect of Spanish on my L1, Lorna’s post (above) captures this ‘reverse interference’ very nicely. It is fairly well-attested in the literature, but is not something I fear or wish to avoid. I’d rather by plurilingual than monolingual!

October 7th, 2013 at 6:21 am

Hi, Scott

How to commit the new chunks to memory IS the ten-million-dollar question, I think, and I’m glad you brought it up. The role of memory in second language learning deserves, I think, a little more attention than what it’s been getting in mainstream ELT.

Personally, I have found that (incidental) re-exposure to the same chunk in other contexts can sometimes be as effective as output-oriented practice. But that’s me, of course.

October 8th, 2013 at 6:33 pm

Hi Luiz – how to commit them to memory, yes. For what it’s worth, there’s a nice book of activities designed for that very purpose by Seth Lindstromberg and Frank Boers: Teaching Chunks of Language: From noticing to remembering (Helbling 2008).

October 7th, 2013 at 4:39 pm

I have never studied Spanish but I have picked up (out?) and memorized numerous phrases, often from listening to songs/poems. Like Karenne, I have also learned common conversational fillers. I can and do produce the phrases and fillers fluently and with very good pronunciation. Unfortunately, my efforts have resulted in little if any grammar acquisition, so in conversation in Spanish all I can do is hop from phrasal island to phrasal island.

Incidentally, my ability to pronounce my chunks well is more of a curse than a blessing. It misleads Spanish-speakers into thinking I have a good command of the language, with the result that they do not grade their Spanish.

October 8th, 2013 at 2:17 pm

Hi Scott, I am really enjoying your new blog.

I would suggest your next notebook have no lines, just plain paper. Why be constricted by what some faceless publisher decided in advance would be the right-sized space for you, to help you write straight? A home-made, personalised notebook is even better: get a wad of A4 and two pieces of card for front and back cover, hole-punch them all and tie together, ideally with wool. Why? If you use a metal ring binder, once you’ve got a few books, they won’t lie flat on top of each other. (I’ll make you one and send it to you if you’s like!)

For years now, I’ve got my students to make their own notebooks. I feel it fits perfectly with a teaching unplugged methodology.

Finally, here’s a Spanish language plant lesson:

David

October 8th, 2013 at 6:35 pm

Thanks for the tip, David. Actually I’m rather fond of my notebooks, which are Italian and have a somewhat retro look (see picture on the ‘Back to School’ post). But I like the idea of crafting my own, too!

October 8th, 2013 at 7:15 pm

Sorry, yes, I totally agree. It was more the blank pages that I wanted to emphasise.

October 8th, 2013 at 6:20 pm

Hello Scott

I also kept a (less eloquent) diary of my classroom experiences as an intermediate student of Spanish

an extract

‘I notice so much of the langauge my teacher uses -lovely expressions, often at the start of an utterance, maybe some sort of subjunctive verb form embedded in a great combination of words.. …but too fast for me to be able to take it down. I’ll ask her to go back, ask her what she said but she’ll have lost it. Gone! Like gold. Lost in that moment of communication.”

As a teacher, I started highlighting some phrases of language I was using as I chatted with my students (immediately popping it on the board without interrupting the flow of conversation too much – a technique I picked up from my fantastic DELTA tutor at IH Barcelona – Neil Forrest).

Capturing the expressions I used in their natural habitat, often got across the more slippery pragmatic sense of a phrase and the high frequency nature of these chunks of language meant that they often re appeared later in a class.

October 8th, 2013 at 6:39 pm

Thanks, Richard – yes, the teacher is (or can be) a hugely rich source of formulaic language, and language which, as you point out, is richly contextualised and often repeated. As I mentioned earlier, one of the first teachers I had when I arrived here peppered her lesson with ‘vamos a ver’ (let’s see now), something I never forgot. The potential for exposure to chunks by the teacher perhaps could be exploited more.

October 9th, 2013 at 3:52 pm

I love this simple technique Richard. It reminds me of a student I used to teach who would always take ages to get going with any of the pairwork speaking activities that I set up in class. He’d always be busily writing things down instead of talking to his partner and it used to frustrate me immensely until I found out what he was writing – which was chunks of language that I’d used in giving the instructions. This taught me a lot about the value of my own speech as comprehensible input and the need to give learners opportunities to notice it.

October 12th, 2013 at 10:43 am

Reblogged this on Blogging the Sotsuron and commented:

Check out Scott Thornbury’s post on the importance of learning phrases. He believes that they “offer a shortcut to fluency, accuracy and idiomaticity”. The sources he cites are also very good, so don’t forget to check the references, too!

November 9th, 2013 at 5:58 pm

Hi Scott,

I am really enjoying this blog! You mentioned, probably in another part, your experiences at Spanish schools. Also Lorna described her experiences at Sevilla University. I have several experiences (I should call them “attempts”) of learning German. Last year I had a few days between two conferences and decided to learn a bit more of German in Vienna. In the first class I could understand only a little –or nothing- but I was having a lot of fun with the teacher trying to make learners follow the exercises of the photocopies and the female learners asking “Was sagt “living together” (in English with a strong accent of the country to where each one belonged) auf Deusch?” and other practical things. In the break I conducted research and discovered that the female students had Austrian boyfriends and were learning German to improve communication with them. The following day I was sent to another class, probably because of my level but most surely because I did not have an Austrian sweetheart, which seemed to be a requirement for that class. New class, new research. There I discovered that the students were trying to learn German in despair so as to get a job. Then, most of them were absent or late for being at/ coming from / going to a job interview. Not much learning in terms of language acquisition but a lot in terms of human contacts. The last day I had my little success with the exam and the speech. My big success was the last evening, for the first time I used the language in the street: to ask a policewoman about the tramway stop and to order the food at the restaurant.