Language learning is often a case of taking two steps forward, then one step back.

Language learning is often a case of taking two steps forward, then one step back.

In fact, lately it feels more like one step forward and two steps back. It’s as if I were right back where I started. Being out of direct contact with Spanish speakers for a total of four weeks in the last two months has not helped. And a couple of negative experiences have had the effect of all but erasing my new-found confidence. Or, at least, they have exposed just how fragile that confidence is.

For instance: we are invited to a friend’s birthday party. There are lots of people we don’t know, and we are the only non-native speakers, a situation that I would normally have avoided at all costs, but which I am feeling less apprehensive about than usual, thanks to my recent Spanish ‘growth spurt’.

The initial chit-chat goes OK, but the preponderance of Catalan is daunting, and I start to worry that I won’t get much conversational mileage out of my refurbished castellano.

I am seated next to someone I don’t know, and I fluff the introductions so I don’t even catch his name. I know I should initiate some small talk but I am pole-axed with anxiety. How to begin? How to continue? Will we understand one another? And, more importantly, will he want to talk to me, once he realizes the risks that conversation with me involves? And so on. So I orient myself away from him and towards the conversation that is going on further up the table. Nobody else is talking to him either, but by now too much time has elapsed to make starting a conversation seem natural and unforced. I pray to God the meal will be over quickly.

Later, a number of us have gathered outside in small groups, where the greater mobility afforded by standing takes some of the tension out of doing small talk. The topic, unsurprisingly, is smoking. I start to describe the draconian anti-smoking measures I’ve just witnessed in Australia. A friend who happens to be passing raises a laugh by teasing me about my pronunciation of a particular word. Once again, I am reduced to silence. I feel I’ve been transported back 25 years.

Two failures; two steps backward.

How to characterize these two incidents in terms of the research into SLA?

The incapacity to initiate conversation (and this happens a lot) directs me to the literature on what is called ‘willingness to communicate’ (WTC). Researchers, such as MacIntyre et al (1998 and 2011), argue that the willingness to communicate to a specific person at a specific time and place is the result of a whole constellation of social and psychological factors, some of which are inherent traits (e.g. shyness) and therefore resistant to manipulation, and others, such as one’s current state of self-confidence, which are situation-specific: ‘The state of self-confidence blends the influences of prior language learning and perceived communicative skills with the motives and anxieties experienced at a particular moment in time into a state of mind broadly characterised by a tendency to approach or avoid the L2 “right now”‘ (MacIntyre et al, 20111: 83-84). Given that, in my Spanish classes, WTC was never a problem (in fact, I rapidly assumed the role of class clown), why am I afflicted by the lack of it in social situations such as the one I have described?

The question led me to look beyond psycholinguistics and explore sociology, specifically Erving Goffman’s performative theory of social interaction, as articulated in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959).

Goffman tellingly makes the point that ‘life may not be much of a gamble, but interaction is’ (p. 243). Why? Because it is through social interaction that one performs oneself. But not in the sense that the self is the cause of the performance; rather, it is its product. ‘The self, … as a performed character, is not an organic thing that has a specific location, whose fundamental fate is to be born, to mature, and to die; it is a dramatic effect arising diffusely from a scene that is presented, and the characteristic issue, the crucial concern, is whether it will be credited or discredited’ (p. 253). Pennycook (2007: 157) makes a similar point: ‘A performative understanding of language suggests that identities are formed in the linguistic performance rather than pregiven’. The problem is, then, that the self that I think I present in Spanish is a necessarily diminished one, and one that not only embarrasses me but (possibly worse) will embarrass my interlocutor.

‘The crucial concern is whether it [the self] will be credited or discredited’. My unwillingness to communicate stems from a fear of being discredited; my friend’s mockery of my accent seemed to vindicate the fact that this fear is well-founded.

And yet, there are second language learners who seem to be immune to such threats to self. Pico Iyer (1992: 101) describes just such a one:

And yet, there are second language learners who seem to be immune to such threats to self. Pico Iyer (1992: 101) describes just such a one:

Sachiko-san was as unabashed and unruly in her embrace of English as most of her compatriots were reticent and shy. … She was happy to plunge ahead without a second thought for grammar, scattering meanings and ambiguities as she went. Plurals were made singular, articles were dropped, verbs were rarely inflected, and word order was exploded – often, in fact, she seemed to be making Japanese sentences with a few English words thrown in. Often, moreover, to vex the misunderstandings further, she spoke both languages at once…

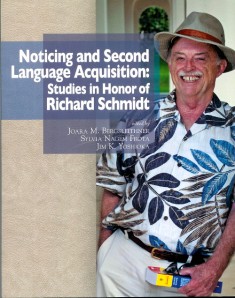

And, in a new book that celebrates the work of Richard Schmidt (Bergsleithner et al, 2013: 5), Schmidt recalls another fluent Japanese user of English, the famous Wes:

Why do people think his English is so good when he doesn’t use prepositions, articles, plurals, and tense? I think it’s because when people talk to him and listen to him, they don’t notice that he doesn’t use them.

In his 1983 study, Schmidt attributes this illusion of accuracy to Wes’s WTC: ‘It seems that his confidence, his willingness to communicate, and especially his persistence in communicating what he has in mind and understanding what his interlocutors have in their minds go a long way towards compensating for his grammatical inaccuracies’ (p. 161).

¡Ojalá que yo tuviera la misma confianza!

Bergsleithner, J.M., Frota, S.N., & Yoshioka, J.K (eds) (2013) Noticing and Second Language Acquisition: Studies, in honor of Richard Schmidt, Honolulu, HI.: NFLRC.

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, New York, NY: Doubleday Anchor.

Iyer, P. (1992) The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto, London: Black Swan.

MacIntyre, P.D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K.A. (1998) ‘Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation,’ Modern Language Journal, 82: 545-562.

MacIntyre, P.D.,Burns, C., & Jessome, A. (2011) ‘Ambivalence about communicating in a second language: A qualitative study of French immersion students’ willingness to communicate,’ Modern Language Journal, 95, 81-96.

Pennycook, A. (2007) Global Englishes and Transcultural Flows. London: Routledge.

Schmidt, R. (1983) ‘Interaction, acculturation and the acquisition of communicative competence,’ in Wolfson, N., and Judd, E. (eds) Sociolinguistics and Second Language Acquisition, Rowley, MA.: Newbury House.

November 10th, 2013 at 9:05 am

Hi Scott,

Fascinating post and one that resonates for me in particular in my own Spanish (and previously French). I have passed the DELE C1 exam, and was actually supposed to sit the C2, but changed my mind to guarantee a pass (how’s that for misplaced confidence?!), and yet there are times when I simply cannot speak Spanish to any level at all, never mind something approaching advanced (I briefly describe one such episode in the first half of this post: http://eltreflection.wordpress.com/2013/01/21/the-spanish-acquisition/). The situation you describe at the party is one I would probably have run a mile from, perhaps actually not even going to the party for fear of being there and being mute, my WTC in serious negative numbers (I have declined invitations to things before on these grounds, though obviously made up a better excuse..).

Like you, I have thought about this a lot and I’ve got it down to something about control, I think. When I speak English, I am in total control of how I come across (the self I create) and the way I use the language. This is also true in Spanish or French when speaking with those less proficient, and so I have no problems in those situations. However, when with those more proficient (or more confident, perhaps) or with native speakers, the reverse is true – I think I subconsciously feel I have no control at all and at times am almost rendered mute (I actually just can’t think of even the simplest thing to say at all) with zero WTC. The worst situation is actually sometimes with a proficient non-native speaker and a native speaker, when I will literally be silent unless directly addressed and then will most often probably answer in three words or less or in English, desperately trying to get the other non-native speaker to take over the conversation and yet not come across as sulking or give some other anti-social impression. I feel this chimes with what you wrote about Pennycook and Goffman – an inability to control the self presented and so a diminished one being the risk which, perversely, leads me to have no WTC in the moment and hence create the most diminished self possible as a paradoxical form of pre-emptive self-defence. Just speak dammit! Anyway, the point of this paragraph was actually to ask if you’d come across any notions of control in your reading?

Much as I admire Sachiko-san and Wes, I hate them! I have friends like them – people who abound communicative confidence – and I think I would sell my grandmother to be one of them. What use is a good knowledge of the imperfect subjunctive if you can’t say “hi, I’m Chris, I work at IH”? Maybe I’ll start a support group…

Chris

November 10th, 2013 at 12:33 pm

Thanks, Chris: it’s nice to know that I’m not alone!

I agree that there is a sense of loss of control, loss of agency, even, which does seem to be implicated in my unwillingness to communicate. In this sense, the issue is less psycholinguistic than psychological, and maybe I need a therapist, not a teacher!

In fact, some scholars have suggested that choosing silence rather than speech is a kind of reversion to our pre-linguistic infancy. In her book Silence in Second Language Learning, Collette Granger (2004), taking a psychoanalytic line, argues that “there are ways in which the process of second language acquisition can be mapped onto L1 acquisition in terms of psychical effect. Each process interferes with and changes, but does not fully destroy, the self that preceded it, and that interference is unconsciously experienced as a loss” (p.80). Hence the silence.

She goes on to suggest that “the silent period in some second-language learners might be a kind of psychical paralysis, a temporary freezing, a complex combination of an inability to articulate and lowered self-regard. And perhaps this possibility offers us a way to imagine silence as symptomatic of a loss, ambivalence and conflict that accompany a transition between two languages, a psychical suspension between two selves” (p.62).

November 11th, 2013 at 5:33 pm

Hi Scott,

The point you make, however much in jest about needing a therapist and not a teacher is something I Have thought about before. I really don’t think it has anything to do with my Spanish per se as it’s been the same from elementary to advanced. In a way, it was easier the lower the level – I love saying random words in Tagalog to the Filipinos here and I do not speak Tagalog other than isolated strings/lexis – as there’s less to lose face at (I think).

More interestingly, that quotation at the end of your reply is really fascinating. I must get a hold of that book somewhere. “psychical paralysis” is exactly what happens to me and, if it is linked to notions of the self, the self presented and agency, would make sense that it happens in Granger’s terms. It’s just a shame this adult silent period can last, oh, 10 years and counting, rather than the usual couple in the kids…

Thank you very much for sharing that.

Chris

November 11th, 2013 at 9:57 am

Nice post, btw, Chris. Wish I’d thought of that title, though (The Spanish Acquisition!)

November 11th, 2013 at 5:34 pm

And thanks! I might well have thought of title before the post and so just had to write something as its connotations are pretty apt. Glad you liked it, both the title and the post.

November 10th, 2013 at 10:17 am

Dear Scott – such was the subject of my talk at BESIG yesterday: the adult, his fears and dogme. Most pertinent here are the three persistent adult fears, which we all have and which surface most agonisingly in new or unfamiliar situations – the fear of being ignored/dismissed/excluded, the fear of being judged incompetent and laughed at and the fear of not being liked, because our “openness” is reduced. As teachers we can provide the space where those fears are reduced, but how do we ensure the fears stay suppressed in the big bad world?

November 10th, 2013 at 12:38 pm

Thanks, Candy… yes, the classroom cocoons us from the threats to self we experience in the ‘real world’. How can it prepare us for them? Maybe by completely de-prioritizing accuracy, and not only tolerating but encouraging the kind of fluent pidgin that made Sachiko-san and Wes acceptable interlocutors? Just a thought.

November 10th, 2013 at 12:56 pm

CHILL OUT Scott about your accent….Actually I became quite proud that when I speak Romanian with a British accent everyone notices. they think it’s cool. Do you want to sound like a Catalan speaking Spanish?Can’t think of anything worse….!!!!!!!

November 10th, 2013 at 1:59 pm

Philip, I have no illusions about achieving a native-like accent. The point of the story (and I realise I didn’t make it clear) was that my Spanish was negatively evaluated and in public – it could have been grammar, lexis, anything – it just happened to be pronunciation. The effect was to reduce me to silence.

November 10th, 2013 at 6:36 pm

Grrrrrrr! If people would just THINK before criticising one’s attempts at speaking another language – even in fun. It has devastating effects on the learner – and sometimes even the teacher. One of my students constantly grimaces when I say his name or says, ” Ugh! Horrible.” I now call him by his surname, because that apparently passes muster even in my “horrible” accent. Can’t be doing with it.

November 10th, 2013 at 6:58 pm

Yes, Candy – the number of people I’ve crossed off my Christmas card list because of explicit or implicit criticisms of my Spanish is legion. ‘HOW long have you lived here?’ is one of the least subtle.

November 10th, 2013 at 1:40 pm

Hi Scott. I haven’t managed to comment much on this new blog yet or follow the discussions, but I’m finding the posts fascinating – really interesting insights into learning. Strikingly, these posts reflecting on your learning highlight not only that there’s not one way that will work for everyone but also that there’s not one way that will always work for an individual learner.

This post on confidence is particularly interesting because confidence seems to be such a crucial part of learning and confidence using the language is a desired outcome in itself. I’d much rather a learner tell me that they were more confident using English as a result of coming to my groups than that they now understood the present perfect.

Increased confidence is something many learners report when asked about the difference learning has made to their lives. As you experienced, however, learners also talk about feeling more confident and competent in the learning group but are less able to communicate in other contexts. As Candy asks, “As teachers we can provide the space where those fears are reduced, but how do we ensure the fears stay suppressed in the big bad world?”

This is such an important question. If it’s not enough for learners to develop and improve in the classroom for them to be able to use the language in real situations, then what are we missing? How can we better connect classroom experience to language use in other contexts. For a while, I organised a series of events and activities where my ESOL learners could get together with other people from the local community and have the opportunity to communicate in a supportive environment. These seemed to work well for all members of the community, but there were still learners who were reluctant to come along because everyone would be speaking English! So it seems I’m still missing a step – a step that helps to overcome (or get around) whatever causes that unwillingness to communicate. I imagine it has a lot to do with what Chris describes as a lack of control in how he comes across.

Why do we put so much stock in how we say something when it is probably more what we say that has an impact on our interlocutors? In a conversation, people listening to us are generally more interested in content than grammatical accuracy and only in pronunciation if they can’t understand us. Aren’t they? A high level of competence is not needed for personality to come across. We know this from working with language learners. We understand them and know them as people even when we have very little shared language. In some contexts, we can be boring and inarticulate in langagues we are compentent in. I once had someone drive off on me while I was doing my very best go give directions in Dutch. But, giving directions in English is far from a strong point of mine. When we’re using another language, do we focus too much on what we can’t do, rather than what we can. Do we compare ourselves unrealistically to those around us and find ourselves lacking? Would we be better to focus on what we can do, what we’ve thus far achieved, and on what we’ve learned in a situation? Is that realistic?

November 10th, 2013 at 6:38 pm

“How can we better connect classroom experience to language use in other contexts?”

How, indeed, Carol. See my response to Candy above for one suggestion (i.e. de-emphasize accuracy in favour of fluency). Another might be to simply role play a lot of high risk encounters: e.g. you are sitting next to someone at a dinner party who you may have met in the past but don’t remember anything about. Or: You encounter a neighbour in the elevator, and have just one minute to make small talk.

At another level (and this relates more to your final paragraph), as teachers we need to avoid, at all costs, sounding or acting as if we are patronizing our students, thereby suggesting that they are somehow retarded. If my teacher, however well-intentioned, treats me like a 5-year-old, I will become a 5-year-old.

November 11th, 2013 at 11:51 am

I completely agree with you about avoiding being patronizing but I’m a wee bit concerned that this point relates to my final paragraph. If it came across that I was suggesting telling people that their language is good when it’s not, that they’ve made progress when they haven’t, or that any aspect of their language is good enough, I didn’t mean that.

November 11th, 2013 at 1:40 pm

No, Carol, that’s not what I understood from your comment. Now that I re-read mine, I’m not sure what it was you said that triggered that thought! Perhaps I was picking up on your point that interlocutors tend to focus on meaning not form, and therefore teachers should too, and not just focus on it, but respect it irrespective of the form it comes wrapped in. Hope that makes sense!

November 10th, 2013 at 3:18 pm

Dear Scott.

I know exactly how you feel. I’m myself very self-conscious in these situations and any sign of ridicule can put me off immediately. What I’ve found very useful is the opportunity to socialize via social media. I know it’s not exactly the same (no pronunciation errors come into play) but it’s helped me to gain more confidence in interacting with users of the target language. And I believe it’s a big step towards being able to communicate in L2 in general.

Hana

November 10th, 2013 at 6:43 pm

Hi Hana… yes, social media do indeed offer an alternative means of interaction where the threat to face is much less acute. I kind of regret that Second Life never really took off because it did seem to offer a ‘safe world’ in which you could ‘be Spanish’ (or German or Japanese etc) behind the mask of another identity.

November 10th, 2013 at 8:12 pm

Second Life? Hmmm, interesting. However, I think it’s your true identity, not hiding behind a mask, that helps you step out of your comfort zone. What I meant is that interaction in social media, as opposed to face-to-face, gives you more time to think about what you want to say, how you want to say it and who you want to talk to…

November 10th, 2013 at 10:07 pm

Yes, I agree, Hana… that tiny moment of reflection before you hit SEND makes all the difference between coming across as vaguely articulate vs a yammering idiot!

November 10th, 2013 at 4:43 pm

Hi Scott, this blog with reflections on one’s foreign language learning is truly fascinating.

Yes, Carol, I agree with you in that interlocutors are more interested in what we say than in our grammatical accuracy. However, in some cases we are required to produce accurate utterances. For example, “teniwoha”, Japanese particles: if we don’t use the right particle the interlocutor might fail to understand who did what for whom. Japanese particles make me cry (probably as many times as English prepositions did).

Pronunciation is a long road towards a place I can never reach. I feel very embarrassed when people do not understand what I say. In English, I have a particular preference for RP, I don’t know why. I used to make short trips to the UK, twice or three times, contacted an institute beforehand and arranged for a certain number of pronunciation classes. When I returned from one of those “Emma Thompson courses” as I called those occasions, I went to the JALT conference: four people the same day told me “Your accent … your accent … you are from France!” How funny, it seems I got rid of my Spanish accent and now I have a French one.

Your pronunciation, Scott, is very good, you pronounce the plosives “p” “t” in a very soft way. I did not hear you speak much in Spanish but I got a very good impression. Did anybody fail to understand you? Probably the room was noisy or your interlocutor wanted to re-confirm what you had said.

November 10th, 2013 at 6:54 pm

Hi Cecilia, Thanks for your comments, and welcome to the blog! I wonder if we overestimate the miscommunication that might result from lack of formal accuracy – even your Japanese particles! I worry excessively about getting the gender of articles wrong (la fuente? el fuente?) but the impact on intelligibility is zero. So why do I worry? Because I don’t want people judging me as being a stupid ‘guiri’. But my pronunciation is going to give me away anyway … so why do I worry? Maybe it would be better to aim for the kind of communicative efficiency that Wes achieved, regardless of accuracy.

(“Emma Thompson Courses”: LOL!)

November 10th, 2013 at 10:45 pm

“A friend who happens to be passing raises a laugh by teasing me about my pronunciation of a particular word. Once again, I am reduced to silence. I feel I’ve been transported back 25 years.”

As an American, non-native speaker of Spanish, there is one thing that I have learned over the last 14 years living in Mexico. The notion that someone else “reduces us to silence” is not a problem with an interlocutor (i.e., the native speaker), but rather with us (i.e., non-native speaker). Others do not cause us stress…we generate our own stress ourselves.

We need to inform (English) language learners that living in another country to learn another language takes courage, patience, and understanding…and not necessarily in that order. Take understanding, for instance. Language learners living within the target culture must understand that invariably others will tease. We either choose to accept this as a form of feedback based on our current (not fixed) performance, or we choose to take offense (or reduce to silence, etc.). With courage and patience, we take ongoing positive and negative feedback (based on both positive & negative evidence), both implicit and explicit, and we continue to thrive to improve.

I tell my English language learners to expect to look foolish sometimes. Realize that most people are good and that living in a new culture can sometimes be hard work. Sometimes it takes accepting the fact that others will tease…it’s usually those folks who don’t appreciate the process of learning a new language and culture. Regardless, my advice is to don’t take yourself or the situation too seriously, take risks, embrace looking foolish at times, and try to enjoy the experience of living in the target country, culture, and language by forming as many healthy relationships as possible.

November 11th, 2013 at 9:37 am

“Don’t take yourself or the situation too seriously, take risks, embrace looking foolish at times, and try to enjoy the experience of living in the target country, culture, and language by forming as many healthy relationships as possible”.

Good advice. Benjamin. On the subject of teasing, it may be of use to show learners how Penelope Cruz responds graciously to Letterman’s ungracious teasing:

November 11th, 2013 at 10:29 am

Hi Scott, I quite agree with Benjamin. I’d like to add that your efforts towards learning Spanish say a lot of your respect for the people of the foreign country where you live. You don’t expect others to speak your language but you work to learn theirs so as to understand and be understood.

November 11th, 2013 at 10:31 am

Hi, Scott,

I have not read all the comments, and may be I am repeating info here, but anyways.

From my experience and the one of adults around me, there are three practical approaches to social situations that could give confidence:

The first advice I got was to objectivize the culture of the L2: the parameters for politeness differ from culture to culture, right? And what may sound rude to an Anglosaxon, may be totally OK for a Latin. I believe it is even more complex for foreign men in Latin countries; I think it would be rare to hear a Spanish speaker making jokes about a women’s accent, or a Spanish woman making jokes about your accent…it is common among men, though, as a way to compete or build rapport (or both). If the L2 culture becomes an object, and you an oberver, then it is easier to ignore when required.

Second, widening the way we built our identity: usually people build their identities based on what they can do or what they know. Generally speaking, thinkers (professors, writers, etc.), particularly, identify themselves with what they know and can do intellectually. I think. And they get their social status out of that. I see in my class with my 60+ students that, although quite smart, men are very restricted by that social status. However, women do not build their identity here based on their competency (smart is not sexy here), and they get status from being open, communicative and humble, therefore, they are the most participative of them all, because they do not lose anything if they make mistakes. Assuming one’s self as a learner and accepting that this part of you take over your social life from time to time is acceptable. It does not make you become a diminished version of your self but it brings out a different side of you. A curious one, a hungry one, a ludic one. That is the beauty of speaking in another language. You get to develop more dimensions of your self. You expand.

And third, and this is more practical, to set up objectives: in a social situation we just want to have fun and have interesting conversations, but if we are not having fun because we are over-cencerned with the communication process, then we need to make that a priority in the social situation: today I’ll listen more and make open-ended questions, today I’ll tell a joke, today I’ll get socratic everytime a person says something I don’t agree with and I cannot reply to, today I’ll use the three phrases I prepared to reply to the guy that makes fun of my accent (that one was from a friend). Everything else that happens will not be relevant. To see every social situation takes away some spontaneity, and it is a good way to use the stress and adrenaline we feel at those moments.

November 11th, 2013 at 9:55 pm

Hi Danya… thanks for your insightful comment. The point about culture is interesting, and one that hadn’t occurred to me in relation to my own WTC, but does go some way to explaining the ‘fish out of water’ feeling I had at that birthday party, and hence my vulnerability.

Also, the point about social status is well made, and this explains my own inhibitions speaking Spanish in the context of my work-related activity, e.g. at conferences, even in small-talk situations (like when I met you in Japan!) I have to say that I feel a lot less self-conscious in Spanish-speaking countries that are NOT Spain: not sure why this is, except possibly a feeling (probably unfounded) that the Spanish judge ‘bad Spanish’ more harshly than they do in Chile, for example.

And that’s great advice, about setting objectives. I have already decided that, this week, I’ll initiate at least one conversation a day. I started in the elevator this evening, with one of the neighbors, and ended up standing on the landing with her, talking about mortality for ten minutes!

November 11th, 2013 at 10:35 am

Sorry for my grammar mistakes…it seems I rely too much on my computer’s corrector.

November 12th, 2013 at 6:11 am

Hi Scott, I kept thinking of your wish to have the same confidence as Wes. We have to build the confianza, and that takes time, patience and work. I have been thinking of what I do to overcome my own embarrassment and also help students to overcome shyness and use corrections constructively.

Cling to the good things. I would normally tell a student: yes, this word has a little mistake but look at your previous sentence, it is perfect. Or don’t worry so much about the pronunciation of “arroz”, it will eventually be all right in a near future, on the other hand your pronunciation of “corazon” is very good. And no, I am not patronizing them, I am just trying to build something on a positive ground. Candy mentioned about a student that grimaced at her when she said his name. It would have been so nice for both of them if he had just said: “Why don’t you call me XX(an easy nick name), all my friends call me that”.

FME (from my experience). In the teachers’ evaluation, in one class with 45 students, many of them wrote about my explanations and instructions being clear but one of them wrote that I need a Japanese teaching assistant because my Japanese is not enough (how many steps back is this?) I try to remember the good things and I keep the negative one not for depression (and for counting how many steps back) but for working even harder with the language.

Turn the negative into positive and think that it was fairly positive from the very beginning. How about thinking that people asking you how long have you been living in Spain want to know just that, how long, and not something else (like a reference to your level of the language).

FME. Once after a presentation an American colleague told me, laughing, that it was cute the way I pronounced “focus”. I felt so terrible. But she was right: I realized that I had not checked the phonetics of the word. The positive thing is that since then I know that it takes a schwa.

Praise yourself for you little great achievements. You could speak for 10 minutes about an abstract topic. If that is not a pillar of confianza, then tell me what it is.

If, at a certain moment we are “reduced to silence”, use that time to speak inside our heads. I try to imagine situations or topics and what to say in those situations and how to respond about those topics. This is something I practice with the students to help them feel confident for speaking without depending on a written text.

I am not sure if this makes any sense …Now I have a question: do you think we can build “confianza” by ourselves? Do we depend on good comments? Can we be immune to external shots?

November 12th, 2013 at 5:22 pm

Thanks for your encouragement, Cecilia, and no, I don’t find it patronizing in the least, because it is advice that clearly comes from both an inspired teacher and an experienced learner. Nevertheless, it is sometimes hard to accept that,as one scholar so memorably put it, in order to become a wit in a second language, you have to be a half-wit first!

As for the question ‘HOW long have you been here?’, there is no doubt as to its pragmatic force when it follows hot on the heels of such elementary mistakes as ‘una problema’ o ‘¿cómo es tu padre?’ Jaja.

November 12th, 2013 at 4:03 pm

Hi Scott,

Thanks for the frank and insightful reflections. I can certainly relate to your experiences here.

You say, “In this sense, the issue is less psycholinguistic than psychological, and maybe I need a therapist, not a teacher!” While the comment is no doubt somewhat tongue-in-cheek, I can’t help feeling the ‘therapeutic aspect’ of teaching does matter. Weary teachers often complain that they are not trained therapists and should not be expected to be, and I can sympathise with that; nevertheless, creating a non-threatening atmosphere where students feel valued, secure and willing to take risks appears to play a significant role in learning. (Your blog post on ‘rapport’ explored this nicely.) It seems to me that successful teachers often mimic this therapist-patient rapport by ‘aping’ therapist-like behaviour and discourse: posing Socratic questions, eliciting relevant ideas to explore, providing non-judgemental, constructive feedback, affording silence for personal reflection etc. And even though, as you are right to remind us, classrooms are often artificial places that hardly prepare students for the cut-and-thrust of real-life encounters, perhaps one role of the teacher is to help ready learners for these real-life challenges by nurturing a space where they can feel safe to try out and experiment with language in preparation for the real thing (the question here though is whether there will be a natural crossover from the classroom to real operating conditions).

Would you go along with the notion that good teachers are, in a loose sense, good therapists too? Or should we insist on strictly separating teaching from therapy?

November 12th, 2013 at 5:29 pm

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Wez. As for your last question, I have always been a bit uncomfortable with methodologies that co-opt the discourses of therapy, because I’ve never felt that as teachers we are equipped to deal with the possible consequences. And often these discourses emanate from the outer fringes of therapy, to boot – e.g. shamanism and NLP. Nevertheless, I do agree with you that the successful teacher (instinctively, perhaps) draws on interpersonal skills that are probably those of a good therapist, the ability to listen being one, and the ability to create a supportive and trusting relationship being another. I may be venturing into this territory in next week’s blog!

November 13th, 2013 at 6:15 am

I know exactly how you feel. I sometimes feel hesitant to speak Japanese in front of anyone but friends because I feel like they’re just waiting for me to make a mistake so they can jump in and say “ah, see, Japanese is so difficult for foreigners”. It becomes a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, as I get so anxious over not matching the stereotype that I end up matching it quite well. You might expect people who have tried to learn another language would be more sympathetic, but sometimes they actually seem more eager to put down people trying to learn their language. It’s disappointing but perhaps revealing of some important facts of human behavior.