I am compulsively devouring phrases. I gobble up expressions like me da pena (it upsets me) and qué buen rollo tiene (how nice he is). It’s not just my reading of the literature on phraseology that impels me. It’s a gut-feeling that these phrases offer a shortcut to fluency, accuracy and idiomaticity.

I am compulsively devouring phrases. I gobble up expressions like me da pena (it upsets me) and qué buen rollo tiene (how nice he is). It’s not just my reading of the literature on phraseology that impels me. It’s a gut-feeling that these phrases offer a shortcut to fluency, accuracy and idiomaticity.

As a youngster I was a nerd avant la lettre, and used to collect phrases from books I was reading, which I would then try to work into writing assignments at school (what now would be called plagiarism). Richmal Crompton’s Just William series was a particularly rich source. I remember co-opting the expression ‘in my official capacity’, much to the bafflement of the teacher, since I had no official capacity whatsoever.

But, even if misapplied in this instance, it was probably a sound learning strategy, and certainly one that is now a fundamental tenet of ‘the lexical approach’. As Pawley and Syder (1983) were among the first to argue, pre-fabricated phrases confer not only idiomaticity (in the sense that they make you sound more target-like) but they also aid fluency: pulling down whole phrases off the mental shelf represents big savings in terms of processing time.

More recently, researchers into both first and second language acquisition have been arguing that a ‘mental phrasicon’ not only contributes to fluency but also feeds the acquisition of grammar. According to this view, a fully syntacticalized grammar is (at least partly) constructed out of, and synthesized from, a stock of memorized phrases.

As Nick Elllis (2003, p. 67) puts it, ‘the acquisition of grammar is the piecemeal learning of many thousands of constructions and the frequency-biased abstraction of regularities within them’. In other words, memorize a chunk like ‘you must be kidding’, and you not only have a useful conversational gambit, but you are getting the raw material, in prototypical form, out of which you can extract ‘you must be joking’. It’s a short step to ‘it must be raining’ and ‘they must be closing’.

This is true for first language acquisition and, arguably, for a second language too. ‘From the perspective of emergent grammar … learning an additional language is about enhancing one’s repertoire of fragments and patterns that enables participation in a wider array of communicative activities. It is not about building up a complete and perfect grammar in order to produce well-formed sentences’ (Lantolf and Thorne, 2006, p. 17).

(How I wish that that quote were emblazoned across the gates of our leading publishers and examination bodies!).

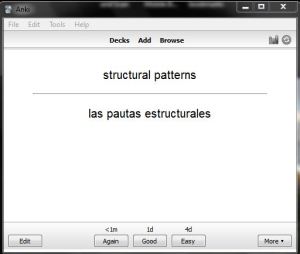

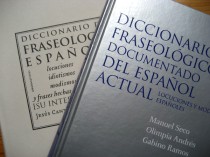

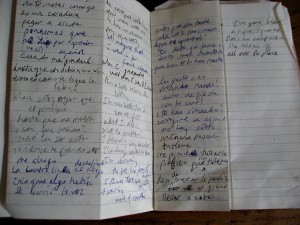

Accordingly, I decided from the outset to keep a notebook of phrases: ones that came up in class, or ones that I noticed in my out-of-class reading. I reinforced my stock of phrases by reference to two fat Spanish phraseological dictionaries. I keyed these all in to Anki, an excellent tool to aid memorization, which digitally replicates Paul Nation’s ‘word cards’ technique, randomizing the sequence, and calibrating the time lapse between items, on the principle of ‘spaced repetition’, according to your own assessment of the accuracy of your recall. (For more on Anki, see this link).

Accordingly, I decided from the outset to keep a notebook of phrases: ones that came up in class, or ones that I noticed in my out-of-class reading. I reinforced my stock of phrases by reference to two fat Spanish phraseological dictionaries. I keyed these all in to Anki, an excellent tool to aid memorization, which digitally replicates Paul Nation’s ‘word cards’ technique, randomizing the sequence, and calibrating the time lapse between items, on the principle of ‘spaced repetition’, according to your own assessment of the accuracy of your recall. (For more on Anki, see this link).

The problem is that there didn’t seem to be any real selection criteria, and hence no organizing principle, for the phrases that I was collecting and attempting to memorize. The dictionaries I consulted gave no indication as to the relative frequency of the phrases nor their register, although one of them at least had examples taken from authentic sources. But, basically I was choosing anything that sounded like it might be useful, especially those phrases – like no le caigo bien (He doesn’t like me) or yo tengo claro que… (I’m sure that…) – that would confer a degree of idiomaticity, without being too colloquial.

In light of the reconfigured objectives mentioned in the last post, i.e. the focus on presentation skills in Spanish, I decided to limit my ‘phrasicon’ to chunks that might be useful in terms of their relevance to the twin fields of language and learning, as well as chunks with high discourse functionality. That is to say, I wanted words and phrases that would help me talk about language teaching and that would also help organize and signpost this talk.

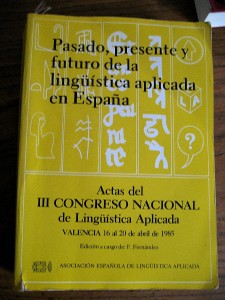

But where to find them? By chance, rootling around in a second-hand bookshop in Barcelona, I came across a copy of the proceedings – in Spanish – of a conference on applied linguistics, convened in Valencia in 1985. A quick glance confirmed that what applied linguists were talking about in 1985, such as puntos gramaticales (grammar points) and un enfoque comunicativo (a communicative approach), is still very much what they are talking about now. Moreover, although the papers are (obviously) in the written mode, there seemed to be a good number of discourse markers, such as en primer lugar (in the first place) and veamos un ejemplo (let’s look at an example), that might be equally useful for giving semi-formal spoken presentations.

But where to find them? By chance, rootling around in a second-hand bookshop in Barcelona, I came across a copy of the proceedings – in Spanish – of a conference on applied linguistics, convened in Valencia in 1985. A quick glance confirmed that what applied linguists were talking about in 1985, such as puntos gramaticales (grammar points) and un enfoque comunicativo (a communicative approach), is still very much what they are talking about now. Moreover, although the papers are (obviously) in the written mode, there seemed to be a good number of discourse markers, such as en primer lugar (in the first place) and veamos un ejemplo (let’s look at an example), that might be equally useful for giving semi-formal spoken presentations.

So, using this book as my ‘corpus’, I created two decks of word cards in Anki: academic collocations, and academic discourse markers, to which I added a third called academic sentence frames, which aims to capture constructions with variable slots that might offer templates for a degree of creativity. E.g. no hay motivo para pensar que… (there’s no reason to think that…) and lo que es importante subrayar es… (what is important to underscore is…’

I’ve been reviewing and supplementing these three decks while on planes and in airport lounges, as I travel round Australia on a conference junket. Having the Anki app on an iPad is ideal for this. Apart from anything else, you can synchronize the app with your home computer, keeping both up-to-date with new entries.

Is it working? Yes and no. Recall of the phrases seems good in the short-term, but if I leave them a day or two, many of them have to be re-learned from scratch.

I suspect that the only way of making them stick is to force some kind of production, preferably in context. But what? Maybe I need to write, rehearse and even record short (e.g. two-minute) segments of talks that embed as many of the phrases as possible. Any thoughts?

Ellis, N. (2003) ‘Constructions, chunking and connectionism,’ in Doughty, C. and Long, M. (eds.)The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, Oxford: Blackwell.

Lantolf, J. and Thorne, S. (2006) Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pawley, A. & Syder, F. (1983) ‘Two puzzles for linguistic theory: nativelike selection and nativelike fluency,’ in Richards, J., & Schmidt, R. (eds.) Language and Communication. Harlow: Longman.